A 100-year-old sign is discovered in Poland, and with it, an entire family.

Introduction

Until recently, I had no real interest in seeing Poland. My ancestors rarely spoke of the old country, or their reasons for leaving in 1906, and there really wouldn’t be much of an emotional connection for me in their hometown.

The last remaining relics of their way of life could be counted on a few fingers. The old cemetery is now a forest, and there are no gravestones. The empty shell of the building where they once worshipped is one of the only visible traces of their culture.

Last year, a Polish anthropologist learned of the recent discovery of a barely-legible name painted above the sealed doorway of a pre-war grocery store. She wrote about the enigmatic sign, and eventually the story found its way into a regional news article that someone casually shared with me.

No one ever imagined that 5,300 miles away, a man in Oregon USA (me) would read about it, thanks to Google Translate, and would recognize the name of his cousin on that sign.

My cousin and her husband were simply two names on my family tree. I knew their names and the years of their birth, but nothing more.

Because my great-grandmother Minnie had left Poland many years before WW2, I never really focused on the siblings she left behind. I became determined to learn if there were any living descendants of her sister and brother-in-law, whose name was on the sign – to let them know that I had a postcard of sorts from their ancestors.

A Family Photograph

I eventually found four descendants: two sisters on the West Coast of the US, and a man and his mother on the East Coast. The West Coast siblings weren’t aware of their East Coast cousins, and vice versa, but all of us were amazed to see this name from our past.

One of my newfound cousins, Eddie, shared a ninety-year-old family photograph belonging to his mother. The older gentleman was the person painted on the grocery sign. I knew that his wife was my great-grandmother’s sister. Together, they were surrounded by their large family in pre-war Poland. Only six names were known for certain. The rest were guesses.

During the next few days, I found myself looking at the photograph over and over again. When I closed my eyes, I could still see their faces. I speculated about their relationships to each other. It seemed likely that some were murdered during the Second World War, but perhaps not everyone.

For those who didn’t survive, I wondered if this photo might be the only visual evidence that they were ever here on Earth.

I knew that there were fifteen personal stories inside this photograph. The faces of the family looked back at me from across the years as they sat beside each other in Konin, Poland one day in 1931. Eighty years after the war, those faces, some of them nameless, seemed like fifteen pieces of a shattered urn. I felt compelled to put them back together again, and to somehow acknowledge them.

I met my cousin Eddie in Boston in the summer of 2022, and during the next several months, we attempted to figure out the names of everyone in the photo. We excitedly traded emails any time either of us made a discovery, and gradually we identified nearly all of them. I say nearly, because there were a couple of educated guesses. But we came to some conclusions based on who was standing next to who.

After we finally had their names, Eddie and I worked for months to learn the fates of everyone in the image. Their stories were comprised of gut-wrenching cruelty and incredible luck.

How the photograph survived the war is a miracle in its own right.

When my great-grandmother left for New York, she joined her two brothers in the New World. She left her two sisters and their families behind in Poland. If anyone had talked her into staying home rather than sailing across the Atlantic, I would almost certainly not be here today.

I decided that I needed to travel to Poland to see the sign with my own eyes, and to pay homage to the cousins who didn’t or perhaps couldn’t leave.

Perhaps I’d be able to walk along the river of my ancestral hometown, to retrace the footsteps of my great-grandparents, and if I squinted hard enough, to maybe catch a fleeting glimpse of the world that they left behind.

Family Collection – All Rights Reserved.

The Sign’s Journey

Damian Kruczkowski, director of the Konin Public Library, first noticed the sign around 2017, while he and his sister were out photographing old balconies. It’s hard to imagine that anyone would notice the sign if they weren’t looking for it. It’s under the balcony of a weathered tenement building, just above where the original entrance would have been. The lettering, barely legible today, reads:

SKLEP SPOŻYWCZY (GROCERY STORE)

LAJB SAJDLIC (LEIB SEIDLITZ)

To the left of the balcony, the initials of the owner, L.Z., and the year 1912 stand in sharp relief against the pale plaster wall.

Damian recognized that the name Lajb was Jewish, and so was the spelling of Zajdlic, rather than the traditional German “Seidlitz.” The discovery of the sign was significant because so few remnants of Jewish Konin exist today. In the 1930s, Jews comprised roughly 25% of the town’s population. Out of 3,000 living there when the Germans invaded Poland in 1939, only 46 returned after the war, but they were gone within a few years. Today there are only a few, if any, in a town of 71,000. So to Damian, it was almost like a minor archeological find.

Magdalena’s Project

The sign and its significance got wider publicity when Magdalena Krysińska-Kałużna, a Polish anthropology professor, approached Damian about his knowledge of pre-war Konin and its Jewish community. She had begun a project called “Jewish Konin, a Place Beyond the Map,” and was writing about the history of sites in the city, and the families that lived and worked in those places. Damian’s discovery of the sign came as a surprise to her, given how many years she’d lived in the town.

Magdalena’s interest in Jewish Konin was influenced initially by British author Theo Richmond’s book, Konin, A Quest. The prize-winning book was published in 1995, and it provides a detailed description of the town before the war, based on interviews with survivors.

Her project began with a desire to transcribe the mental map of Jewish Konin that she carried around in her head every time she crossed a certain square or passed by surviving buildings from that era. Her intention was to remind the contemporary inhabitants of the town about the people and the culture that vanished during the war.

Early in her project, she talked with a friend whose mother was a young girl when the war began. The mother had many Jewish childhood friends, and as she got older, she sometimes thought she was in pre-war Konin. She got to the point where she sometimes didn’t recognize her own family, but she still knew the names of her long-gone friends and neighbors.

During the war, when her Jewish friends came to her window to say goodbye before being relocated to a ghetto in another city, she was afraid to come to the window. She thought the Germans might take her too.

She regretted it for the rest of her life.

Like many of us who fail to ask questions about our parents’ childhoods, Magdalena was too late to tap the memories of her friend’s mother about the war and about Konin’s Jews, but it made her more determined to save what information could be saved, before it was too late.

The sign was mentioned by Magdalena in several journalistic pieces associated with her project, and eventually showed up in a regional online newspaper article about the lost cemeteries of Konin, that I came across because a friend thought I might be interested.

Discovery of a Familiar Name

The news article, which was written by Robert Olejnik in the LM Regional News Portal, was obviously written in Polish. Skimming the text and pictures, I could see that the cemeteries no longer exist today. I was about to close the browser window when the words “Lajb Zajdlic” caught my eye from the bottom of the second page.

There wasn’t an immediate connection, but the name felt familiar. It looked like Seidlitz, a cousin’s name. It nagged at me overnight after reading the article, and the next morning I explored my family tree to see if there was any connection. Seidlitz…. Ah — Zajdlic. I didn’t realize that it was the Polish spelling of the same name. It was my great-grandmother’s sister Rosa (Rojza) and her husband Leib (Lajb) Seidlitz.

I immediately contacted Damian and Magdalena, to share the news that someone on the other side of the world recognized this faded name below the balcony. Naturally, they were quite surprised.

An Undelivered Postcard

When I think about the journey that the sign has taken — from its inception as banner for a new business, to its survival through decades of neglect, to its discovery and publication in Poland, and finally to a computer screen in Oregon — it was like finding a postcard that was mailed nearly a century ago, but never delivered; a message of sorts from a man and his family that nearly disappeared from the earth, as if they never existed.

Although I never met anyone in this branch of my family, the message felt like it was for me. “We were here” was part of the message, and I was determined to learn more.

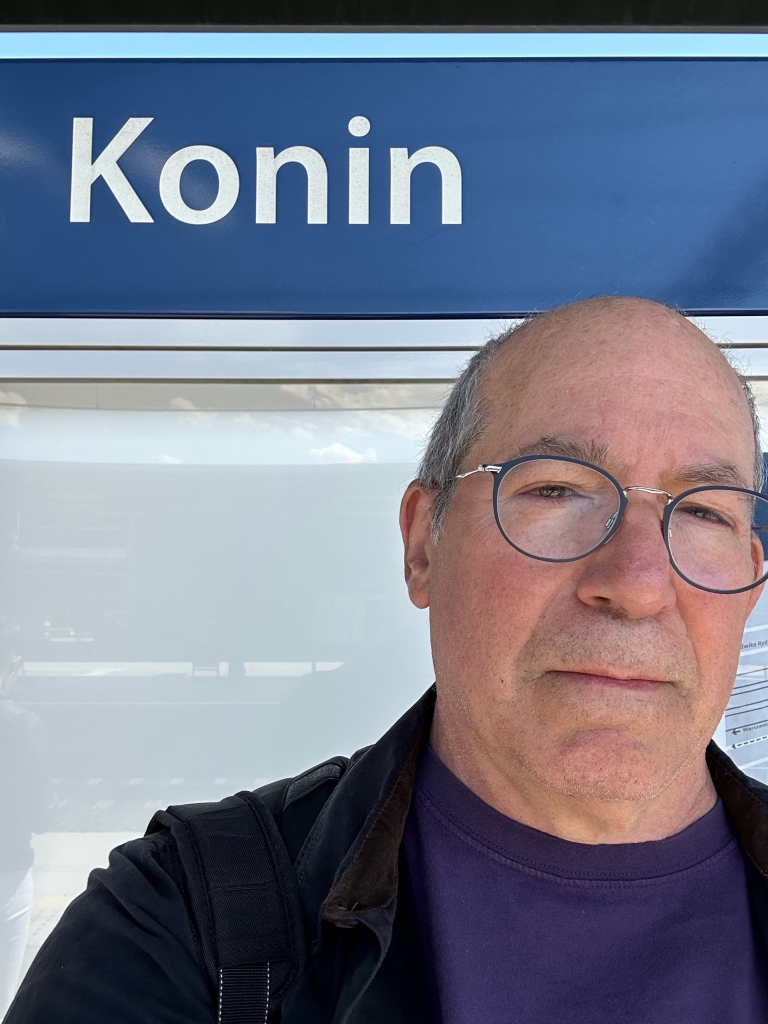

A Visit to the Old Country — Day One

Before going to bed on my first night in Konin, I opened Theo Richmond’s book once again. I had read much of it before going to Poland, and it was especially helpful in preparing me for many of the sights I was about to see.

The next morning, I was on my own. The first place I visited was the sign for the grocery store. I don’t know who, if anyone, lived in the vicinity during its time as a grocery store. Leib had other successful businesses, and we don’t know where the grocery fit into his enterprises. But there were families living inside the property now, so I tried not to gawk in front of the doorway for too long.

I crossed the street to see where Theo Richmond’s ancestors lived – nearly across the street from Leib’s grocery store. The two families undoubtedly knew each other.

Still, I had traveled thousands of miles to see the sign, so I took more photos from across the street. After a few minutes, a man stepped out of his driveway to ask what I was taking pictures of. At first, I was worried that he was upset, but he seemed to be genuinely curious.

I explained that my cousins had a grocery store in this building before the war, and he smiled. He grew up directly across the street just after the war, and his father lived there for years before that. His father surely would have known Leib and his family.

He was eager to tell me about the woman who lived next door, still in her 90s, and how she would have known Leib and Rosa (we were unable to reach her). He told me about the place two doors down that was a candy shop, and another place in the other direction that was a kosher butcher.

The next day, he went into his house to retrieve an old photo of his family in a horse-drawn wagon, taken roughly across the street from the grocery store. It provided a glimpse of the view that Leib and his family might have seen on any given day, frozen in time.

Afterwards, I walked up the main street toward the center of the old town and marveled at the checkerboard pattern of beautifully restored old buildings, contrasting with some that look rather sad. Most of the buildings looked original, and I found myself wondering which side of the street my family would have favored. Other than the colorful treatments on some of the restored buildings, they absolutely would have recognized the scene 100 years later.

I saw the old market square (Tepper Markt, the center of Jewish life), but it does not look anything like its former self, a bustling hub of merchants and markets. Many of the buildings were replaced after the war, and the square itself is fairly ordinary today.

One building on the southern side of the square had a particularly photogenic patina, and while I was photographing it, a car pulled up to the curb and a man rolled down his window, speaking to me in Polish.

I told him I didn’t speak Polish, and he didn’t speak English, so we agreed on German, which was a stretch for me.

He asked if I wanted to buy the building. I declined, and when he asked why I was photographing the building, I summarized my story. He asked me to wait while he parked his car, and then he returned, gesturing, Come. Come. Follow me.

The next thing I knew, I was in his office with his wife and granddaughter, and he was offering me coffee, tea, or mineral water. He motioned for me to sit down, and the three of them looked at me expectantly from the other side of the desk after he asked me to tell the story again, from the beginning.

When he heard about the sign, and how I came from Oregon to see it, he said, Mein Gott (my God in German) as he shook his head.

We introduced each other — his name is Konstanty. We stepped out to the sidewalk again, and he was eager to point out several places that few people would know about: where the rabbi lived, and various stores around the old square. Then he told me if I came back the next day, he would take me on a tour. I gratefully agreed.

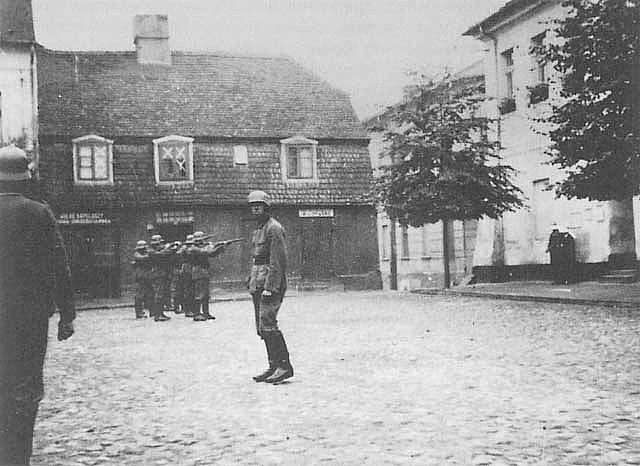

Later that afternoon, I stopped to see the bullet holes that have been preserved in the wall on the main square, Plac Wolności. It was at this spot, a few days after the German army marched into town in September 1939, where a randomly chosen Catholic man and a Jewish man were executed in front of the townspeople, just to instill fear and assert authority.

That afternoon, I met up with Magdalena, who reminded me that I had agreed to give an invited talk about my family to anyone who was interested. It was to be held at the empty synagogue. She had made an announcement on Facebook, and it had received a few RSVPs. I could handle that, I figured.

Day Two

The next morning, I met up with Konstanty, and we walked to various buildings near the old market square. There was an apothecary that’s been in continuous operation since 1900. He assured me that my great-grandparents would have shopped there. He introduced me to the pharmacist, who stepped out from behind the counter to shake my hand.

Then we went to a bookstore, where he introduced me again, and kindly bought me two picture books of old Konin.

For Dust You Are, and To Dust You Shall Return

We hopped into his car and drove to the site of an old Jewish cemetery that no longer visibly exists. It was now a young forest.

The gravestones were removed by the Nazis during the war, in order to clear the land for a military training ground. We don’t know if the stones were used to pave streets, as they were elsewhere in Poland, but nothing remains of them today, except for a handful that are in a local museum.

Konstanty told me later,

Despite the efforts of the Germans during the war to wipe out not only the Jews, but all memory of them from the face of the earth, they luckily failed. We remember.

I stopped for a moment to ponder the dilemma that my great-great-grandparents were probably buried among these trees, but I didn’t know where to place a stone of remembrance. I tossed a small rock into the forest, which felt sacrilegious, although my intentions were good.

I picked up three stones to take home with me: one to place on the grave of my Konin-born grandmother who is buried in Los Angeles, and the other two to place on the graves of my great-grandparents, who are buried in New York.

Jewish law teaches that the body should be returned to the earth from which it came. “For Dust You Are, and To Dust You Shall Return.”

Somehow, it seemed right that a tiny part of Poland should be with them.

As we parted, I told Konstanty about the event at the synagogue at 5pm, in case he wanted to stop by. I thanked him, but he insisted that there was no need. He said that he didn’t do it for me, but for history.

As I walked back to town, I realized that he had been waiting for someone to tell these stories to. He’s in his mid-70s, and has carried this knowledge around with him for most of this life. Konin is not a town that sees a lot of tourists, and my guess is that he probably hadn’t encountered many people who would be genuinely interested in hearing the stories. But I certainly was.

The Synagogue

I met Magdalena and Damian at the synagogue to help them with the setup. I got a lump in my throat, which was unexpected, as I walked through the original wooden doors to the synagogue; the same door that my great-grandparents would have used as they went into the same building, built in the 1820s; the place where they were undoubtedly married.

The building had been looted in by the Germans in 1939 and emptied of its contents, which were burned outside. It served as a stable and a storage facility during the German occupation, and then more recently as a library. It is now empty again, but the interior has been painted, and light fixtures now adorn the walls. It’s not fully restored – it needs more financial support – but it was easy to appreciate the beauty of the place, even as an empty shell of its former existence.

The Presentation

Gradually the synagogue began to fill with people. The folding chairs that we brought were quickly taken. I texted my wife that 25 people were there. People began to sit on the floor and lean against the walls. 50 people. They kept coming in, and some of them went to the second floor, overlooking the temple. I estimated around 80 people who came in at 5 o’clock on a Friday evening to hear the story.

One woman, whose ancestors would have known Leib and Rosa, travelled 150 miles each way from Warsaw. We had four cheerful volunteer interpreters from the high school. Konstanty appeared in the back of the room. There was a journalist and a photographer.

The director of the regional archives, Piotr Rybczyński, spoke about the history of Jews in the town. Magdalena and Damian spoke to provide context to my presentation. Then it was my turn.

As I got up and faced the audience, I looked down at my feet, for a brief moment, and wondered what my great-grandparents would think if they could fast-forward to 2023 and see me talking about them in precisely the same spot where they would have stood beneath a marriage canopy in 1902.

I opened with an introduction to my great-grandparents, and what kind of people they were. When I told a story about Minnie chasing kids around the house with a chicken claw, making clucking noises, someone said “typical Konin.”

I thanked everyone for coming on a Friday evening, told them how beautiful their town was, and what an honor it was to be there.

Then it was time to talk about the photograph of Leib and Rosa and their family.

Eddie and I had tried to recreate the stories of everyone in the photograph, with the limited information we had. We consulted holocaust testimony, personal recollections, memoirs, obituaries, transit documents, books of the dead, news articles, birth records, marriage records, and more.

For decades, knowledge about the members of this family was scattered in dozens of documents, and in the memories of the few people who knew some of the faces in the photograph.

This would be the first time that the fate of Leib’s and Rosa’s entire family was told together, in one place.

In the center of the photograph and of the family are Leib/Lajb (#1) and his wife Rosa/Rojza (#2).

Leib was listed in a 1968 memorial book for the town as having been murdered in the war. Like countless others, we do not really know precisely how, when, or where he died, but we know he was alive when the war began, because there is a photograph of him wearing the yellow star that Jews were forced to wear during the early days of the war.

Jews were murdered in a variety of ways, among them gassing, shooting, burning, drowning or burial alive, exhaustion through forced labor, starvation, epidemic diseases, deprivation of medical care and unhygienic conditions. Some took their own lives, in order to escape arrest and further persecution, or to end their hopeless suffering. He would have been approximately 80 years old at the time.

Rosa is listed in the book as well, but to add to the indignity, her record is missing a first name. She is only referred to as (female) Zeidlitz, married to Leib, of Konin. She would have been approximately 77.

Standing on the far left, we see son Cudek (#3), a former football star who was widely known in the region. A merchant when the war broke out, he was sent to the Ostrowiec ghetto in 1941, and lived until 1943. He was 43 years old when his life was meaninglessly cut short.

A woman we believe to be Cudek’s wife Esther (#4), is sitting next to him, near Rosa. She was sent to the Lublin ghetto in the spring of 1941, and later to Ostrowiec, where she was murdered. She would have been 37.

According to the memorial book, Cudek and Esther had a child, but we don’t have any additional information.

Sitting on the far right is son Saul (#5). Standing behind him is his daughter Tola (#6), and sitting next to him is his wife Helena (#7). Saul died at Auschwitz in 1943, age 51. Saul’s wife and daughter managed to survive by sneaking into a kitchen brigade and stirring a pot of soup with the only utensil they had with them — a spoon.

Helena and Tola were two of the 46 people to return to Konin after the war. They went to the train station every evening for several months, to see if anyone else would return. No one did. Eventually they left Poland.

Standing behind Leib, and to our right, is his daughter Ita (#8) and her husband Jacob (#9). Ita was sent to Ostrowiec Kielecki, and then to Treblinka in 1942, where she presumably died. She was 35. Her husband Jacob, the tall man standing next to her, was liberated from an unknown camp in April 1945. He remarried and emigrated to the US, via Costa Rica.

Standing behind the young child are son Abraham (#10) and we believe his then-fiancee Rose (#11). After they married, they moved to Paris. In July 1939, they made a trip to New York, for what appears to have been a personal visit. In September, when the war broke out, they were on their way back to France. Eventually, he or they were sent to a transit camp near Paris, and even though the camp was later closed and its prisoners sent to Auschwitz, Abraham somehow made his way to Pau in southern France, and eventually to Philadelphia via Portugal. He ended up in Canada, while his wife returned to Paris, where she died in the 1960s. We presume they divorced somewhere along the way.

The second and third people standing in the back are daughter Bluma (#12) and her husband Marek (#13). Bluma was the first woman in her family to graduate from the university in Warsaw. The two young boys in the photo are their sons Avrom (#14) and Dovid (#15).

In the early days of the war, the family was able to hide in a cellar for several months, by paying a reluctant farmer for shelter and a minimal amount of food. This arrangement lasted until the money ran out, and then the farmer turned them in. The family was taken to an unknown concentration camp, and as punishment, the Germans forced them to watch as their youngest, son Avrom, age 12, was thrown into a burning oven alive.

The older son, died of unknown causes on the day his concentration camp was liberated, in the arms of a childhood friend from Konin.

Bluma and Marek survived and ended up in Canada. Several family accounts say that Bluma didn’t speak for a number of years before her death.

One of Leib and Rosa’s sons was not in the photo. He left for Berlin in the early 1920s. He had a furniture shop, and after a mysterious fire, he luckily decided to move to New York rather than to rebuild in Germany.

A Photo Survives the War

I told the audience how I had asked Eddie’s mother where the photograph was during the war. If everyone in the photo was incarcerated in one way or another, how could something like this survive?

As we know, the mother and her daughter on the right side of the photo returned to Konin after the war. They went to the house that they had to leave in a hurry 4 or 5 years earlier, and found another family living it. All of the old houses had new residents. When this particular family moved in, they found a stack of family photos, two silver Sabbath candlesticks, and a set of crystal goblets.

They kept them — just in case anyone ever came back. And they did.

The family let the two women stay with them, and when they sold the house, they shared some of the proceeds.

It would have been so easy for the new residents to throw away the photos. If they had, we would never have had a roadmap for telling this family’s story.

At the end of the presentation, I told them it was my honor to say on behalf of Leib, Rosa and their family, “We were here.”

Afterwards, I was overwhelmed by the number of people who wanted to shake my hand and have their photo taken with me. They were speaking in Polish, trying to tell me that they were touched by the story, but when they realized I didn’t understand a word they were saying, they simply tapped their chests over their hearts, with warm smiles.

The Director of the Archives then took about fifty of the participants on a walk of various sites, culminating in walking a little over half a mile to the former grocery store. It was a surrealistic sight, as everyone gathered in front of the doorway and pointed at the sign, taking photos and making the residents inside wonder what was going on. Even the police drove by and gave us a quizzical look.

As the crowd began to dissipate, I took one long last look up at the sign that sparked my journey to Poland, and smiled. There was that lump in my throat again.

About ten of us walked back up to the old town, and as the sun set over the riverbank, we sat outside and continued to share stories over various tea infusions.

It was a perfect end to an emotional day.

Reflection

I think I was surprised at how curious people were about this vanished world that I barely knew anything about myself. Perhaps they learned some things in school, but because so much was erased, I get the sense that there is a thirst to connect with this aspect of the town’s past.

The first generation of Poles who were born after the war are already in their 70s. It’s not that they forgot anything about the war – they never knew it firsthand.

And now the first generation of the post-communist era have families of their own. They didn’t experience wartime occupation or totalitarianism.

I wondered what role the younger people will play in preventing these kinds of horrors in the future. But as Magdalena succinctly told me,

People who survived the war were tough. During the war, they faced the possibility of death almost every day; of being sent to forced labor in Germany or some other misfortune. We, the middle generation, were brought up on our parents’ memories of the war. We grew up during the difficult times of totalitarianism, where the army and police shot at protesting citizens; where gestures that would cost nothing now could mean, for example, expulsion from school or the loss of a job. Young people, fortunately, do not have such experiences, but inevitably they are less hardened. As a result, there is a risk that they may not notice in time what is at stake.

If…

There was an undercurrent of magic and synchronicity throughout my visit. I marveled at the warm welcome and acts of kindness that I received from total strangers.

The chain of events that led me to see the sign was full of near-misses. Every one of them was a miracle of sorts:

- If Damian hadn’t noticed the sign, the family portrait would have stayed in a photo album in Massachusetts, and the names of the people in it would be lost forever.

- If Magdalena didn’t think Damian’s discovery was interesting enough to write about, I would never have known about it.

- If my friend hadn’t thought to send me the article about the old cemeteries, I wouldn’t have seen mention of the sign.

- If I had closed the article after reading about the cemeteries, I would never have read about the sign.

- If it didn’t occur to me to use Google Translate to read the article, I might have just looked at the pictures and moved on.

- If the family photo had been thrown away by the Polish family who took over Helena’s house, we would never have known how many people to look for, and their fates would never be known.

As it is, we’ll never know their life stories.

That night, I kept looking at the face of the littlest boy in the photograph, sitting safely between his loving grandparents. He could still be alive today. He’d be exactly the same age as my father.

I have a lot to tell my grandson.

I was here.